All of sudden, critical race theory was more than mainstream in America’s law schools. It was mandatory.

Starting this Fall, Georgetown Law School will require all students to take a class “on the importance of questioning the law’s neutrality” and assessing its “differential effects on subordinated groups,” according to university documents obtained by Common Sense. UC Irvine School of Law, University of Southern California Gould School of Law, Yeshiva University’s Cardozo School of Law, and Boston College Law School have implemented similar requirements. Other law schools are considering them.

In 2017, the super lawyer David Boies was at a corporate retreat at the Ritz-Carlton in Key Biscayne, Florida, hosted by his law firm, Boies, Schiller and Flexner. Boies was a liberal legend: He had represented Al Gore in Bush v. Gore, and, in 2013, successfully defended gay marriage in California, in Hollingsworth v. Perry, paving the way for the landmark Supreme Court ruling two years later.

On the last day of the retreat, Boies gave a talk in the hotel ballroom to 100 or so attorneys, according to a lawyer who was present at the event. Afterwards, Boies’s colleagues were invited to ask questions.

Most of the questions were yawners. Then, an associate in her late twenties stood up. She said there were lawyers at the firm who were “uncomfortable” with Boies representing disgraced movie maker Harvey Weinstein, and she wanted to know whether Boies would pay them severance so they could quit and focus on applying for jobs at other firms. Boies, who declined to comment for this article, said no.

That lawyers could be tainted by representing unpopular clients was hardly news. But in times past, lawyers worried about the public—not other lawyers. Defending communists, terrorists, and cop killers had never been a crowd pleaser, but that’s what lawyers had to do sometimes: Defend people who were hated.

When congressional Republicans attacked attorneys for representing Guantanamo detainees, for example, the entire profession rallied around them. The American Civil Liberties Union noted that John Adams took pride in representing British soldiers accused of taking part in the Boston Massacre, calling it “one of the best pieces of service I ever rendered to my country.”

But that’s not how the new associates saw Boies’s choice to represent Weinstein. They thought there were certain people you just did not represent—people so hateful and reprehensible that helping them made you complicit. The partners, the old-timers—pretty much everyone over 50—found this unbelievable. That wasn’t the law as they had known it. That wasn’t America.

“The idea that guilty people shouldn’t get lawyers attacks the legal system at its root,” Andrew Koppelman, a prominent liberal scholar of constitutional law at Northwestern University, said. “People will ask: ‘How can you represent someone who’s guilty?’ The answer is that a society where accused people don’t get a defense as a matter of course is a society you don’t want to live in. It’s a totalitarian nightmare.”

‘Operating in a Panopticon’

The adversarial legal system—in which both sides of a dispute are represented vigorously by attorneys with a vested interest in winning—is at the heart of the American constitutional order. Since time immemorial, law schools have tried to prepare their students to take part in that system.

Not so much anymore. Now, the politicization and tribalism of campus life have crowded out old-fashioned expectations about justice and neutrality. The imperatives of race, gender and identity are more important to more and more law students than due process, the presumption of innocence, and all the norms and values at the foundation of what we think of as the rule of law.

Critics of those values are nothing new, of course, and certainly they are not new at elite law schools. Critical race theory, as it came to be called in the 1980s, began as a critique of neutral principles of justice. The argument went like this: Since the United States was systemically racist—since racism was baked into the country’s political, legal, economic and cultural institutions—neutrality, the conviction that the system should not seek to benefit any one group, camouflaged and even compounded that racism. The only way to undo it was to abandon all pretense of neutrality and to be unneutral. It was to tip the scales in favor of those who never had a fair shake to start with.

But critical race theory, until quite recently, only had so much purchase in legal academia. The ideas of its founders—figures like Derrick Bell, Alan David Freeman, and Kimberlé Crenshaw—tended to have less influence on the law than on college students, who by 2015 seemed significantly less liberal (“small L”) than they used to be. There was the Yale Halloween costume kerfuffle. The University of Missouri president being forced out. Students at Evergreen State patrolling campus with baseball bats, eyes peeled for thought criminals.

At first, the conventional wisdom held that this was “just a few college kids”—a few spoiled snowflakes—who would “grow out of it” when they reached the real world and became serious people. That did not happen. Instead, the undergraduates clung to their ideas about justice and injustice. They became medical students and law students. Then 2020 happened.

All of sudden, critical race theory was more than mainstream in America’s law schools. It was mandatory.

Starting this Fall, Georgetown Law School will require all students to take a class “on the importance of questioning the law’s neutrality” and assessing its “differential effects on subordinated groups,” according to university documents obtained by Common Sense. UC Irvine School of Law, University of Southern California Gould School of Law, Yeshiva University’s Cardozo School of Law, and Boston College Law School have implemented similar requirements. Other law schools are considering them.

As of last month, the American Bar Association is requiring all accredited law schools to “provide education to law students on bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism,” both at the start of law school and “at least once again before graduation.” That’s in addition to a mandatory legal ethics class, which must now instruct students that they have a duty as lawyers to “eliminate racism.” (The American Bar Association, which accredits almost every law school in the United States, voted 348 to 17 to adopt the new standard.)

Trial verdicts that do not jibe with the new politics are seen as signs of an inextricable hate—and an illegitimate legal order. At the Santa Clara University School of Law, administrators emailed students that the acquittal of Kyle Rittenhouse—the 17-year-old who killed two men and wounded another during a riot, in Kenosha, Wisconsin—was “further evidence of the persistent racial injustice and systemic racism within our criminal justice system.” At UC Irvine, the university’s chief diversity officer emailed students that the acquittal “conveys a chilling message: Neither Black lives nor those of their allies’ matter.” (He later apologized for having “appeared to call into question a lawful trial verdict.”)

Professors say it is harder to lecture about cases in which accused rapists are acquitted, or a police officer is found not guilty of abusing his authority. One criminal law professor at a top law school told me he’s even stopped teaching theories of punishment because of how negatively students react to retributivism—the view that punishment is justified because criminals deserve to suffer.

“I got into this job because I liked to play devil’s advocate,” said the tenured professor, who identifies as a liberal. “I can’t do that anymore. I have a family.”

Other law professors—several of whom asked me not to identify their institution, their area of expertise, or even their state of residence—were similarly terrified.

Nadine Strossen, the first woman to head the American Civil Liberties Union and a professor at New York Law School, told me: “I massively self-censor. I assume that every single thing that is said, every facial gesture, is going to be recorded and potentially disseminated to the entire world. I feel as if I am operating in a panopticon.”

This has all come as a shock to many law professors, who had long assumed that law schools wouldn’t cave to the new orthodoxy.

At a Heterodox Academy panel discussion in December 2020, Harvard Law School Professor Randall Kennedy said that, until recently, he’d thought that fears of law schools becoming illiberal—shutting down unpopular views or voices—had been overblown. “I’ve changed my mind,” said Kennedy, who, in 2013, published a book called “For Discrimination: Race, Affirmative Action, and the Law.” “I think that there really is a big problem.”

The problem has come not just from students, but from administrators, who often foment the forces they capitulate to. Administrators now outnumber faculty at some universities—Yale employs 5,066 administrators and just 4,937 professors—and law schools haven’t been spared the bloat. Several law professors bemoaned the proliferation of diversity, equity, and inclusion offices, which, they said, tend to validate student grievances and encourage censorship.

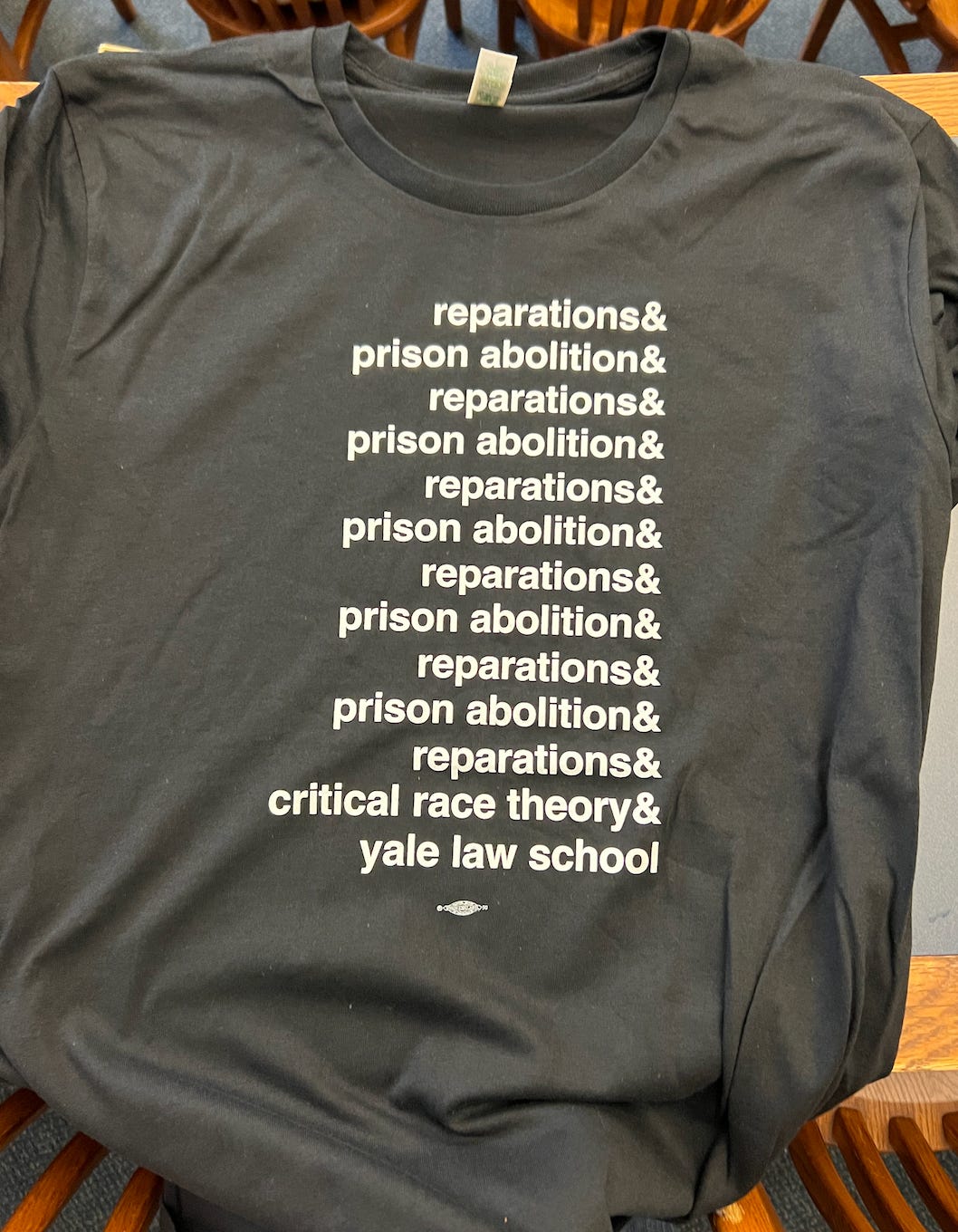

The distinction between DEI and the rest of the administration is often wafer thin. At Yale Law School, the Office of Student Affairs told students in an email last week that they could “swing by” the office to grab a “Critical Race Theory T-Shirt!” The T-shirt repeated the phrase “reparations & prison abolition” five times, Bart Simpson-style, before delivering the kicker: “critical race theory & yale law school.”

Law school deans have further entrenched this culture. In 2020, 176 of them petitioned the American Bar Association to require “education around bias, cultural competence, and anti-racism” at all accredited law schools, which led to the new ABA standards this February.

As the new ideology has been institutionalized, the costs of disobeying it have grown steeper, both for faculty and for students.

At the University of Illinois Chicago, for example, a law professor’s classes were cancelled and his career threatened for including a bleeped out “‘n____’” on an exam in a hypothetical scenario about employment discrimination. (He had used the same scenario for years without incident.)

A Harvard Law professor told me that students face “social death” if they buck the consensus. Students at other law schools—including Yale, NYU, Boston College, Georgetown, and Northwestern—told me much the same thing. “You want to have friends, so you don’t want to say anything controversial,” one Georgetown Law student explained.

At Boston College Law School this semester, a constitutional law professor asked students: “Who does not think we should scrap the constitution?” According to a student in the class, not a single person raised their hand.

Those students and organizations who do dissent often encounter a tsunami of hate. When members of Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law’s Federalist Society chapter invited the conservative writer Josh Hammer to campus in October 2021, the law school’s all-student listserv lit up with invective.

“I’d be completely unsurprised (and in fact, willing to bet) that Joshie Hammer fucks (or at least tries to fuck—he probably was rejected repeatedly) we the trannies in his free time,” one student emailed. “Or—more likely—he just wants (and needs) to get just fucked in the ass . . . Maybe our lovely, idiotic FedSoc board is experiencing a similar dilemma within their own psychosexual selves.”

That was nothing compared to what happened at Yale Law School earlier this month, when the school’s chapter of the Federalist Society hosted a bipartisan panel on civil liberties. More than 100 law students disrupted the event, intimidating attendees and attempting to drown out the speakers. When the professor moderating the panel, Kate Stith, told the protesters to “grow up,” they hurled abuse at her and insisted their disturbance was “free speech.”

The fracas caused so much chaos that the police were called. After it ended, the protesters pressured their peers to sign an open letter endorsing their actions and condemning the Federalist Society, which they claimed had “profoundly undermined our community’s values of equity and inclusivity.”

“I’m sure you realize that not signing the letter is not a neutral stance,” one student told her class group chat. She was upset that the panel had included Kristen Waggoner of the Alliance Defending Freedom, a conservative legal nonprofit that’s won a slew of religious liberty cases at the Supreme Court.

As similar messages clogged listservs and Discord forums, nearly two-thirds of Yale Law’s student body wound up signing the letter.

Stith, the professor who was lambasted for telling students to “grow up,” doesn’t see the pile-on as an isolated incident.

“Law schools are in crisis,” she told me. “The truth doesn’t matter much. The game is to signal one’s virtue.”

The Associates Want to ‘Burn the Place Down’

We don’t need to speculate about how temper tantrums in New Haven will reshape American institutions. The ideas underlying these outbursts have already spread to boardrooms and government agencies.

Last year, NASDAQ demanded that companies listing shares on its exchanges meet racial and gender quotas. Uber and Postmates waived delivery fees from black-owned restaurants. Montana and Vermont gave non-white residents priority access to Covid-19 vaccines.

Some high-profile initiatives have been blocked—for example, the Biden administration’s attempt to prioritize minority-owned restaurants while doling out pandemic relief. But the legal guardrails that once ensured against this sort of tipping of the scales are coming undone.

That was the lesson of Rebecca Slaughter, one of the five commissioners who run the Federal Trade Commission.

In a Twitter thread in September 2020, Slaughter declared: “#Antitrust can and should be #antiracist.”

Then she added: “There’s precedent for using antitrust to combat racism. E.g., South Africa considers #racialequity in #antitrust analysis to reduce high economic concentration & balance racially skewed business ownership.”

Here was a prominent government official—educated at Yale Law School, formerly senior counsel for Senator Chuck Schumer—proposing that a federal agency jettison its mandate (protecting consumers, ensuring competition) in the service of a political goal (narrowing the racial wealth gap) that no one had debated or voted on.

In practice, several attorneys said, that meant a company with a majority-white board could be penalized for something that a company with a majority-black board might not be. The government might even block a merger if the resulting conglomerate would be insufficiently diverse—something that has actually happened in South Africa, the country Slaughter held up as a model. Jobs, plants, investments, market share: all of it was on the line.

“That’s hugely corrosive,” said a corporate lawyer in Virginia, who, like most attorneys contacted for this article, would not go on the record for fear of losing his job. “You see it in all of the worst things we see in Donald Trump. ‘The law means what I say it means. The election was stolen because I lost.’ Once you depart from the idea that we’re all people under the law, it really matters who is in power. That starts to feel like the rule of man, not the rule of law.”

Two weeks after posting her thread, Slaughter appeared on CNBC. “I want to be working to promote equity, rather than reinforce inequity,” she said. She had come to the conclusion that “it isn’t possible to really be actually neutral, nor should we be neutral in the face of systemic racism and structural racism.”

Slaughter’s statement was not a one-off. It captured the zeitgeist not just of post-Floyd progressivism, but of an increasingly large chunk of the legal profession. The idea that lawyers can’t be neutral, that confronting injustice must supersede all else, has eroded the norm that legal representation—like the ability to obtain medical care or buy a train ticket—is something every American deserves.

“Partners are being blindsided by associates who they think are liberals in their own image,” an attorney in Washington, D.C., told me. “But they’re not. The associates want to burn the place down.”

Lawyers at top law firms in New York, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles said they fret constantly about saying the wrong thing—or taking on the wrong client.

“It’s much worse than McCarthyism,” Alan Dershowitz, a professor emeritus at Harvard Law, told me. “McCarthyism was a reflection of dying, old views. They were not the future. But the people today who are imposing litmus tests for who they represent—they are the future.”

When Dershowitz was accused, in 2014, of sexual relations with an underage girl at Jeffrey Epstein’s various residences, he said he had trouble finding representation. (A federal judge eventually struck the allegations from the record.)

Law firms have been known to avoid unpopular clients—Big Tobacco, for example—but the scope and frequency of these evasions have increased, dozens of lawyers interviewed for this story agreed. That’s partly because young lawyers, like the one who accosted David Boies, see representing someone as tantamount to endorsing them.

“It used to be that most lawyers could work for Catholic hospital system even if they were pro-choice,” a recently retired lawyer told me. “But now people just say, ‘I oppose this client, so I can’t work for them.’” (The lawyer had planned to stay at his law firm—one of the largest in the US—for a long time. He told me he retired in 2020 after the firm’s culture became “simply unbearable,” with younger associates excoriating him for being “old and white, and part of the reason we have systemic racism in America.”)

Law firms also worry about losing their corporate clients, which, like many American institutions, have grown more stridently ideological in recent years. “I knew of and heard of clients protesting cases we were taking,” the recently retired lawyer said. “If you were going to do a gun rights case, you would incur the wrath of other clients.”

Since 2011, law firms have been pressured to drop or turn down a long list of clients: fossil fuel companies, foreign universities, a GOP-controlled House of Representatives, employers challenging Biden’s vaccine mandate, and, of course, Donald Trump.

These pressures—both internal and external—have had a chilling effect. If defending anti-vaxxers can cost you business, law firms reason, imagine the blowback of defending a transphobe or a racist.

“It doesn’t even occur to people to take controversial cases,” one lawyer in Washington, D.C., said. Religious liberty cases, for example, are “totally off the table. I wouldn’t even think to bring it up.”

Another lawyer, who specializes in First Amendment litigation, described being forced to turn away a client with far-right views because the firm thought that any association with the client—even if the claims advanced were meritorious—would be bad for business.

The problem, Strossen said, is that rights mean nothing without representation. “ANYONE who doesn’t have access to counsel in defending a right, as a practical matter, doesn’t have a meaningful opportunity to exercise that right,” the former ACLU chief told me in an email. “Hence, undermining representation for any unpopular speaker or idea endangers freedom for ANY speaker or idea, because the tides of popularity are constantly shifting.”

Ken Starr, the former solicitor general who led the 1998 investigation of Bill Clinton, agreed. “At a time when fundamental freedoms are under assault around the globe, it is all the more imperative that American lawyers boldly stand up for the rule of law,” Starr said. “In our country, that includes—especially now—the representation of controversial causes and unpopular clients.”

Undermining the Impartial Judiciary

Another cornerstone of the rule of law is an impartial judiciary. Some judges, however, have begun to see themselves not as impartial adjudicators, but as agents of social change—believing, like Slaughter, that they cannot be neutral in the midst of moral emergencies.

During the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, for example, Massachusetts Superior Court judge Shannon Frison vowed on Facebook to “never be silent or complicit again, in any courtroom or any context.” “As the very keepers of justice,” she said, judges “not only stand with the protesters—we fall with them.”

The Washington State Supreme Court put out a statement recognizing “the role we have played in devaluing black lives,” and encouraged judges to strike down “even the most venerable precedent” if it is “incorrect and harmful.”

Such statements are not mere virtue signaling. They reflect sincerely held beliefs with real-world consequences.

Case in point: the case of Montez Terriel Lee, Jr.

On May 28, 2020, Lee, Jr., then 25 years old, broke into the MaX it PAWN Shop, in Minneapolis. It had been three days since George Floyd had been murdered by a white police officer, about ten blocks south, and the city had been engulfed by riots. As looters grabbed whatever they could find, Lee poured lighter fluid all over the pawn shop. Then, he set it on fire. Outside, Lee raised his arm and clenched his fist. In a video, he can be seen saying, “Fuck this place. We’re gonna burn this bitch down.”

At the time, Lee was unaware that Oscar Stewart, Jr., a 30-year-old father of five, was trapped inside and that he would die of smoke inhalation and excessive burns. A little over two weeks later, police arrested Lee, who pleaded guilty to arson.

Usually, this sort of crime, according to federal sentencing guidelines, would have landed Lee in prison for up to 20 years. But the prosecutor, Assistant U.S. Attorney Thomas Calhoun-Lopez, only asked for 12 years.

In his pre-sentence filing, Calhoun-Lopez portrayed Lee not as a rioter but a protester. “Mr. Lee was terribly misguided, and his actions had tragic, unthinkable consequences. But he appears to have believed that he was, in Dr. King’s eloquent words, engaging in ‘the language of the unheard.’”

The judge, Wilhelmina Wright, appeared to buy that argument. On January 14, she handed down a sentence of just 10 years—even fewer than the prosecution had asked for.

“Motivation is a relevant factor in sentencing, and it was appropriate for the prosecutor and judge to consider the fact that the defendant did not intend to kill anyone when he set fire to the store,” Rebecca Roiphe, a professor of legal ethics at New York Law School, said in an email. But, she added, “Rewarding someone for having the correct beliefs is almost as bad as punishing someone for having the wrong ones. More importantly, a criminal justice system that does the former likely does the latter as well.”

Strossen was more pointed: “For anyone who might applaud the Minneapolis situation, I would ask: ‘How would you feel about a judge who has religious objections to abortion giving a lighter sentence to a pro-life crusaders who attacks clinic property or personnel?’”

Judge Wright’s willingness to tip scales didn’t come out of nowhere. When she was a student at Harvard Law School, she’d taken a class with Derrick Bell, the founder of critical race theory, who asked students to submit written reflections on the assigned readings. Bell published many of the reflections—including Wright’s—in a 1989 article for UCLA Law Review: “Racial Reflections: Dialogues in the Direction of Liberation.”

In one reflection, Wright said that “American liberalism”—especially the liberal “notion that property is neutral”—was “equally” as “damaging” as overt “racial supremacy.” Her chambers are eight miles away from the MaX it PAWN Shop, one of 1,500 businesses—many minority-owned—that were damaged or destroyed in the record-setting riots of 2020.

‘The Anti-Innocence Project’

Minneapolis is a microcosm of a larger trend. As progressives have set about repurposing the law, they seem to have lost sight of the people they insist they’re saving: the poor, the vulnerable, the indigent—including many racial minorities.

Consider the movement to abolish the right to eliminate members of a jury pool.

The so-called peremptory strike allows attorneys, in a trial case, to toss out potential jurors they deem biased. Peremptories, as criminal-defense attorneys see it, offer their least sympathetic clients—those against whom all the cards have been stacked—a glimmer of hope.

The problem, as progressives see it, is peremptory strikes have also been used to disproportionately exclude potential black jurors. Supreme Court Justice Steven Breyer was among the most prominent to call for an end to peremptories, arguing in a 2005 opinion that they magnify racial bias in the legal system. But it wasn’t until the last year or so that the cause gained momentum.

In August, the Arizona Supreme Court announced that the state would no longer allow peremptory challenges at civil and criminal trials. This came after a pair of Arizona judges launched a petition arguing that peremptories perpetuate “discrimination.” The New Jersey Supreme Court is considering a similar move.

It hasn’t gone over well with defense attorneys.

“This is the stupidest fucking thing in the world,” Ambrosio Rodriguez, a criminal-defense attorney in Los Angeles, said. “Is my voice clear just how pissed off I am about this thing?” Rodriguez noted that the peremptory is one of the few tools at his disposal to help “level the playing field.”

“Suppose a woman married to a police officer says she can be fair,” Josh Kendrick, a criminal-defense attorney in Columbia, South Carolina, told me. “I won’t be able to strike her from the jury, even though we all know she can’t really be fair.”

Then there’s the erosion of the principle that one is innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. “The Anti-Innocence Project,” one criminal-defense attorney in San Francisco joked.

Progressive lawyers have become more determined to turn a blind eye to certain defendants while cracking down with even greater than usual fervor on certain crimes. “The same people who are anti-incarceration for some defendants will support life plus cancer for others,” said Scott Greenfield, a criminal-defense attorney in New York. “Good people—which in practice means blacks and Hispanics, regardless of what they did—should be free. Bad people—which in practice means sex offenders and financial criminals—should go to jail.”

In 2019, for example, the American Bar Association nearly passed a motion urging state legislatures and courts to adopt a new definition of “consent” in cases of sexual misconduct that would flip the burden of proof from the accuser to the accused—despite fierce criticism of the standard from legal scholars, and despite some evidence that it has unfairly hurt black, male students on college campuses.

The motion was expected to pass but failed at the last minute, after key attorneys withdrew their support. Even so, nearly 40 percent of ABA delegates voted for it.

This sort of progressive carceralism isn’t confined to sexual assault. After the Rittenhouse verdict, in November, some left-wing legal scholars zeroed in on the definition of “self-defense.” Changing that definition—insisting that whoever was the first to point his gun was the presumptive aggressor—would have made it harder for Rittenhouse to have been acquitted. It would also preempt future Rittenhouses.

Kendrick, the criminal defense attorney, was skeptical. “These reforms aren’t going to be weaponized against white males or the GOP,” he said. “They’re going to be weaponized against criminal defendants.”

Criminal defendants like Stephen Spencer.

In July 2017, Spencer, a black man, endured a series of racist taunts at a bar. When he went outside, a group of white men followed him and shouted: “We’re going to get you, n—–!” Taking them at their word, Spencer turned around, pulled out his gun, and fired, killing one of his pursuers.

A jury acquitted Spencer on all counts. But under a different definition of self-defense—one reverse engineered to put the Rittenhouses of the world in jail—the case could easily have gone another way.

“There’s a real risk Stephen Spencer would be a convicted murderer instead of a free man, because he displayed a lawfully possessed firearm when he was menaced by a racist mob,” a prominent second-amendment lawyer told me.

Brave New World

The old-school liberals, those who have been around for three or four decades, say that none of this was supposed to happen.

Several attorneys called FTC commissioner Rebecca Slaughter’s thread—and her almost off-the-cuff reference to South Africa—deeply unsettling. Of all places, they said, South Africa? Did she know what was going on there? (Slaughter and her assistant did not return calls and text messages.)

In July, there had been rioting, looting, Molotov cocktails, people pulled from their cars and families hacked to death in their homes. The demonstrations had been sparked by the arrest of former President Jacob Zuma, now serving a 15-month sentence for contempt of court. But the real causes had been percolating for decades: a faltering economy, corruption, and the deeply divisive policies of the ruling African National Congress, which Slaughter held up as a model of “#racialequity.”

It started in 1998 with the Competition Act, an antitrust law that effectively required businesses to be partly black-owned. The act was an early example of “Black Economic Empowerment”—race-conscious policies aimed at lifting black South Africans out of poverty.

It was a disaster. Soon, companies were being forced to cede large chunks of their equity to black shareholders, many of whom were well-connected to the ANC. Foreign investment dried up—the regulations imposed huge costs on businesses—and corruption and unemployment soared.

By 2009, Moeletsi Mbeki, a black South African political economist, was warning that South Africa’s race-conscious policies would “collapse” the country. By 2021, South Africa’s unemployment rate was 44%, the highest in the world.

All this had culminated in the riots that killed 300 people and destroyed scores of businesses. This was the country a U.S. antitrust official wanted to emulate.

At stake, said Noah Phillips, also an FTC commissioner, was not just trade or competition but the American justice system itself. How we govern ourselves. What we mean by democracy and the rule of law.

“We should strive to meet the promise that is literally chiseled into the stone of the Department of Justice and courthouses across the country,” Phillips told me. “That is: the law should be applied equally. Deliberately attempting to apply the law in an unequal fashion, based on the preferences of those in power, is inimical to the rule of law.”

On November 12, the FTC released a draft strategic plan for the next five years. One of its main objectives: use the agency’s power to “advance racial equity.”